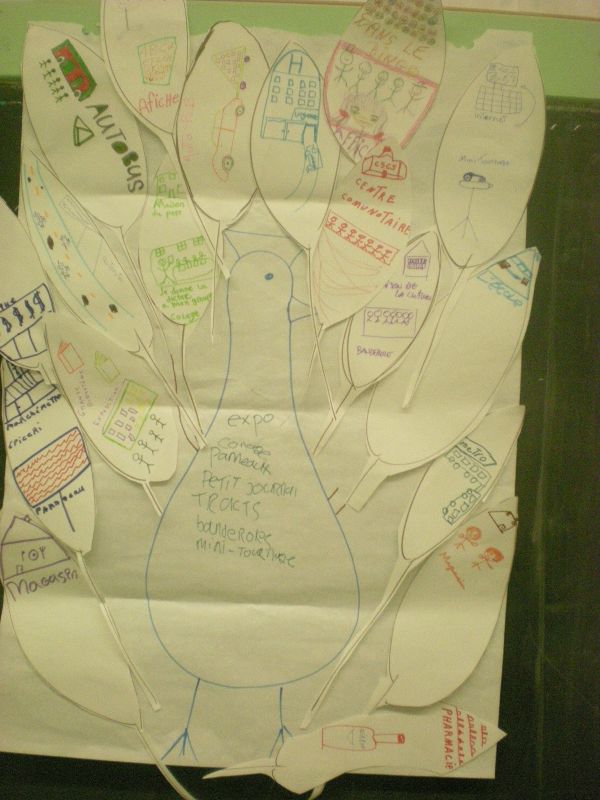

The PAR tools give structure to the process and foster creation of a democratic space. There is a very wide variety of PAR tools, and the choice of tool must be made according to the objective of the process. The best known and used in Quebec in the field of popular literacy are:

- the problem tree, which makes it possible to highlight the causes and consequences of a problem in order to find solutions;

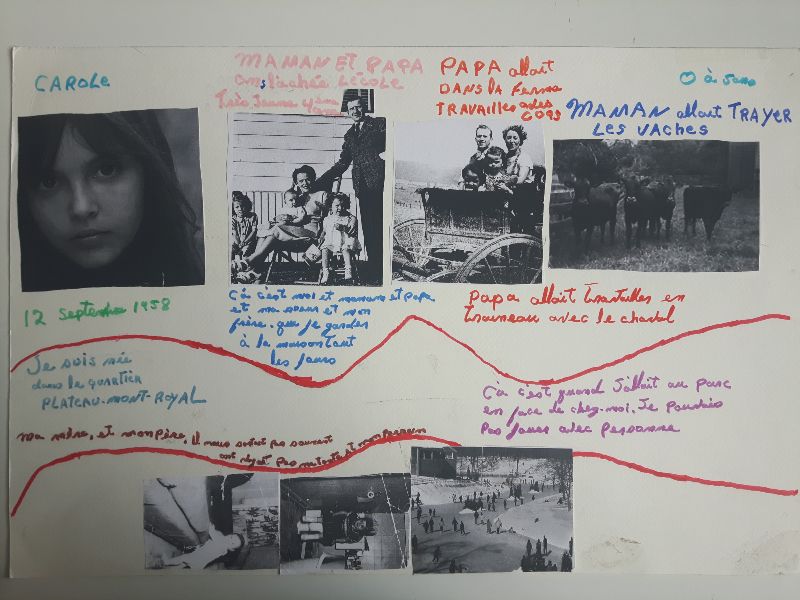

- the river of life, which makes it possible to retrace, through events, the history of a person or a community;

- and the matrix, which enables classification, comparison, prioritization, or evaluation.

The basic principles of Reflect

What does not change, however, are the basic principles of the approach. First of all, like any approach that is part of a participatory approach, Reflect requires time – the idea being to allow everyone, and in particular those who are least at ease, to have their say. It becomes difficult and counterproductive to keep to a precise schedule. Such a process therefore requires a high degree of flexibility on the part of the facilitator and participants.

Moreover, in the context of a Reflect activity, the moderator or trainer is generally called a ‘facilitator,’ because their role is to facilitate individual expression, the exchange of points of view and of everyone’s life experiences. The facilitator initiates the analysis process by proposing activities and visual tools, but also participates in the process by sharing experiences and points of view, while taking care not to position themselves as experts or to gauge the influence of their opinions on the group.

Indeed, Reflect aims to promote local knowledge. The facilitator is there to demonstrate to participants that they have and are able to develop the skills and knowledge to understand the world around them and take action to improve it. The facilitator must be very open, respecting people’s customs and points of reference. They should let people express themselves, even if what they say may seem wrong, imprecise or irrelevant, before drawing these elements back into the discussion. They must also foster a spirit of research through the triangulation of information and by encouraging debate.

Symbolization and consensus

How do we manage to conduct a collective analysis in which people with low literacy can participate fully? This is where symbolization becomes key. Just as each letter of the alphabet is a symbol that has been agreed upon, a convention, in the Reflect approach participants choose and agree on symbols that will represent their ideas. These symbols (drawings or objects) are then placed in a visual tool, as well as in a legend where the meaning of each symbol will be recorded in writing. In this way, participants will be able to review the tools and follow the evolution of the group’s thinking.

To this end, consensus is the second key to the Reflect approach. Consensus makes it possible to distribute power within the group and prevent those who speak more naturally or who are more influential from monopolizing decision-making to the detriment of those who are more reserved. Obviously, this is not always easily accomplished, but it is necessary to develop the habit of working on consensus-building even if it requires time. The haste that often leads us to want to vote leads to frustration and discontent, while the cohesion created by consensus gives greater strength to the mobilization and collective action that will follow.

Conclusion: On the path to innovation

Since innovation is an integral part of Reflect, and our essential task is “to creatively adapt the approach,” I warmly invite you to take ownership of it in your participatory research projects. Not only will it allow you to include everyone, regardless of their literacy level, in your collective research process, but the research experience will itself become a process of social transformation because it will allow people, normally excluded from the public domain, to have their voices heard.

Text written by Amélie Bouchard

Paulo Freire: an inspiration

Reflect is an acronym that stands for Regenerated Freirian Literacy through Empowerment and Community Techniques. Paulo Freire was a Brazilian pedagogue who, from the 1960s onwards, developed a literacy approach aimed at emancipating agricultural workers and, more broadly, effecting social transformation. Paulo Freire’s theory is at the root of the approach adopted by the majority of popular literacy groups in Quebec, at least those who are members of the Regroupement des groupes populaires en alphabétisation du Québec (RGPAQ) such as La Jarnigoine (link to website jarnigoine.com), and around the world. He is internationally recognized as the father of critical pedagogy.